“Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes”

Those are the words from Charles Goodhart’s 1975 paper describing a problem in monetary economics that I once studied at university. It actually (arguably) showed up in its original context in relation to Geoffrey Howe’s monetary policy in the early 1980s, but that’s a story for another time…

The basic concept is as follows. Suppose you break your arm. You know you have an injury because it hurts. Now suppose you take painkillers of sufficient strength to remove the pain altogether. So you’ve fixed the problem of the pain, but now you don’t know how your arm is, because it doesn’t hurt. So how will you know when it’s better? (Assume the x-ray machine is considered unreliable). By controlling the thing you’re observing – the pain, or the lack thereof – it stops being informative.

More generally, when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. And that may be happening in local by-elections. These weekly votes to elect councillors to vacant seats have generally been regarded as better indicators of the state (or rather, the change in the state) of the public mood than Westminster by-elections. The latter can often become a bit of a circus, with huge numbers of politicians, activists and journalists descending on normally safe seats, giving voters the chance (and parties often encouraging them) to “send a message”. That’s born out in the consistent anti-government bias that Westminster by-elections have exhibited for as long as records are available.

The usefulness of council by-elections as a barometer has relied on them not being treated that way. That seems to be changing, with Lib Dem supporters going wild over results on social media, national media coverage in some cases and politicians bringing them up for spinning purposes. The continuing skepticism around polling has also been harnessed by those trying to push a narrative based on “real votes” in preference to the relatively static polls (though in all seriousness, I would put no weight on the commentary of anyone that does this without the appropriate caveats).

We’ve just pulled off a huge victory in #Rotherham – but this can happen in your area too. Join us: https://t.co/uhtmkgT1D2 pic.twitter.com/xxn9SEytJV

— Liberal Democrats (@LibDems) February 3, 2017

And at the same time campaigning has intensified. Activists in all parties have commented on (and posted photographic evidence of) the level of leafletting and other campaign activity. This tends to be amplified by the low turnouts (under 20 per cent is common), which aren’t normally a major distorting factor, but become one if one side makes a vastly greater effort to get out the vote. Therefore, as more effort goes into local by-elections, the risk is that they’re no longer an unbiased barometer.

Turnout also matters in the context of interpreting the EU referendum result. Suppose an area voted 60 per cent Leave on an average turnout of 72 per cent. That doesn’t sound promising for an overtly pro-European party. But that means 40 per cent of voters or 29 per cent of the electorate voted Remain in that area. 29 per cent is usually more than the entire poll in local by-elections and sometimes double it, so it’s not hard to see how turnout can amplify the effect of getting out the vote.

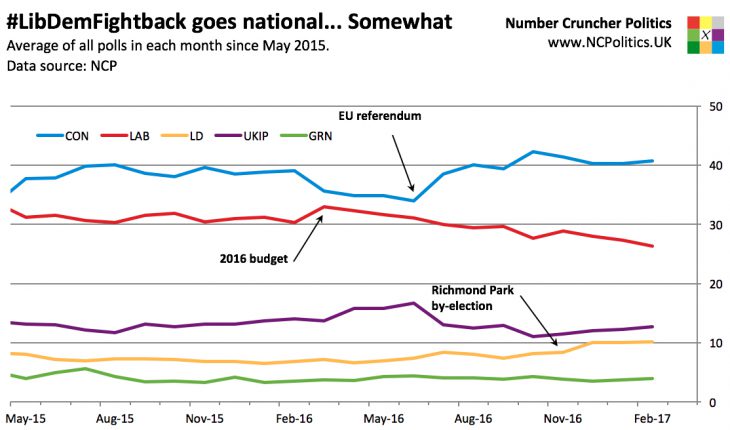

But, back to the question. Is this why the Lib Dems seem to be doing better in local by-elections than in the polls? As I argue in forthcoming piece for this week’s Lib Dem Newswire, it could be, but it could be a couple of other things too.

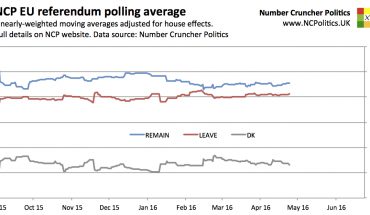

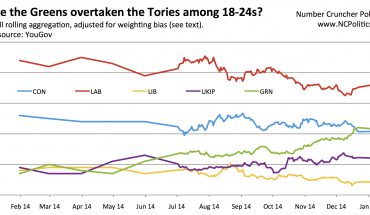

An alternative possibility is a change in the relationship between local and national election results. That wasn’t much in evidence last May, when the gap between national polls and the national equivalent vote in the local elections was in the mid single digits, about where it was during the coalition years (other than when local elections and general or European elections were held on the same day). But it could have changed since the 23rd of June.

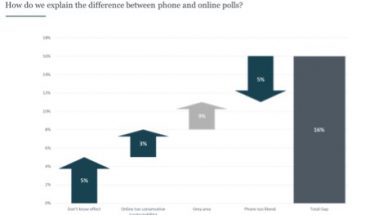

Thirdly, it’s conceivable that polls are underestimating Lib Dem support. Polls have, of course, had their issues lately and Lib-Lab switchers have often been a problem (in both directions). If polls are picking up overly partisan supporters of other parties, it could conceivably create inertia and genuine moves could be understated.

In truth, any of these three scenarios are possible. Many Lib Dems (including Mark Pack) doubt the “Goodhart” theory, though supporters of other parties mention it without being prompted. We’ll have to wait until the next round of locals in May to see who’s right. A breakdown in the relationship between local and national results is possible, but Lib Dems have always done a bit better (as opposed to a lot better) locally than nationally, so this would involve something having changed in a big way. And as for the possibility of yet another polling problem, it shouldn’t be ruled out, but so far there’s little evidence of it anywhere else. I’d want to see an awful lot more proof before jumping to that conclusion.