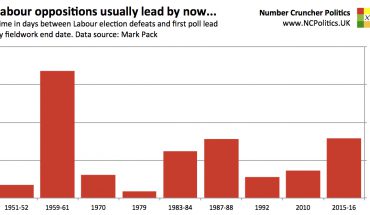

Chris Ship is quoting a Labour source as saying they party is more worried about the Conservatives than UKIP in Stoke. I'd probably interpret that as UKIP doing underwhelmingly in yet another by-election and (as I wrote earlier today in the briefing) the Tories fancying their chances of beating UKIP.

Hard to overstate just how off-the-scale extraordinary this would be. Pretty sure no gov party has ever made a by-election gain from 3rd https://t.co/8BOpe2IhRz

— Matt Singh (@MattSingh_) February 21, 2017

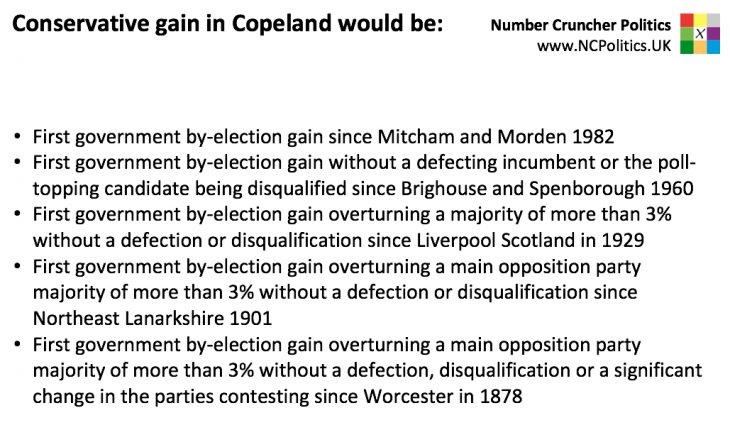

A Tory gain in Stoke would be an off-the-scale event. But I think people are underestimating just how remarkable even a Tory gain in Copeland would be. Since the drag on governing parties in by-elections (even when they have abnormally huge poll leads) is perhaps a bit abstract, I thought it would be useful and interesting to provide a bit of historical context.

As almost everyone will have heard by now, the last time a governing party gained a seat in a by-election was the Conservatives at Mitcham and Morden in 1982, which has created a sense that Copeland turning blue would be a once-in-a-generation type outcome. But if you actually look at the record book and the footnotes, it would be even more unusual than that. The list of previous midterm government gains is a catalogue of quirks, oddballs and wars rather than governing parties simply polling really well (that is necessary but usually not sufficient).

The last example to date, Angela Rumbold’s win in the Merton seat 35 years ago, took place in very odd circumstances, not just politically (it was during the Falklands War) but also electorally. The Labour incumbent defected to the SDP and honoured a promise to his constituency party that he’d resign to recontest (unlike any other SDP defector). That had the effect of splitting the non-Tory vote almost perfectly and allowing the Conservatives to take it on a fractionally reduced vote share.

Before that was Bristol Southeast in 1961. Tony Benn won for Labour in 1959, but was enobled Viscount Stansgate when his father died two years later. In those days that meant instant disqualification from the Commons, but in the subsequent by-election he stood anyway, was disqualified, and Malcolm St Clair, who finished 39 points (!) behind Benn, “won” the by-election without actually topping the poll. (Benn was returned in a second by-election in 1963 after the law changed and St Clair voluntarily stood aside).

You have to back to Brighouse and Spenborough in 1960 to find a genuine case of a government gain without any funny business involving defections or disqualifications. But that was to overturn a majority of just 47 votes. Copeland is not a knife-edge ultra-marginal. At 6.5 per cent, it’s a regular, common garden marginal, requiring a non-neglibile swing to turn it blue.

The last time anyone did that was Labour at Liverpool Scotland 1929 (which wasn’t contested), and the Tories at Hackney South in 1922 (which was). However those were against an Irish nationalist outside of Ireland and an independent liberal respectively. Neither was a governing party gaining from the principal opposition party.

The last time that happened was the Tory gain at North East Lanarkshire in 1901. Yet even that isn’t strictly comparable because the reason for the Tory gain was that the intervention of the Scottish Workers’ Party (which was merged into Labour a few years later) polled 22 per cent of the vote, mostly at the Liberals’ expense, splitting the left.

You can see from all of this how government gains in by-elections aren’t just exceptionally rare, the examples that have occurred are mostly the product of freakish circumstances (to repeat – that means electorally, not merely politically), none of which apply to Copeland.

The last time a governing party gained a seat in by-election by overturning a principal opposition party majority of more than 3 per cent, without a defecting incumbent, a disqualified winner or a material change in the set of parties contesting the seat, was when John Derby Allcroft took Worcester for the Tories on 28th Mar 1878, overturning a 7.6 per cent Liberal majority.

So the Conservatives are trying to do something that hasn’t been done on a genuine like-for-like basis for 139 years, since a time when women couldn’t vote, secret ballots had only been in use for one general election and Keir Hardie wasn’t yet even a union organiser.

Which is not to say that they won’t succeed. But if they do, and Theresa May gains an MP mid term, she won’t have done something that hasn’t been done since Thatcher. She’ll have done something that hasn’t been done since Disraeli.