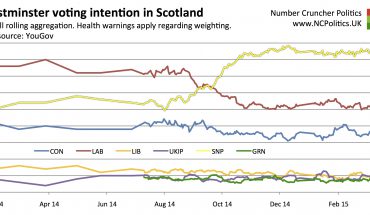

Early on Sunday, ITN’s Paul Brand revealed that a senior Conservative MP had told him that internal Conservative Party polling put the Tories 12 points behind Labour, not the 1-2 points that recent published polls have averaged.

Public polling might put Labour only 2 points ahead of Tories, but one senior Conservative MP told me this week that internal polling shows a 12 point gap. Blue panic.

— Paul Brand (@PaulBrandITV) November 19, 2017

Twitter, of course, got very excited about this. A 12-point Labour lead would be dramatic, given that it would put Jeremy Corbyn in No 10 with a comfortable overall majority. But is it real?

Right now the number one rule for pollwatchers, reinforced by events over the last couple of years, is that almost nothing should be ruled out entirely. But a pretty close second is that when private polls supposedly show something vastly different to public polls, it’s usually nonsense.

First rule of 'internal' polling being spouted as different to 'public' polling is not to believe it. Second rule is to ask BPC to force pollster to publish, as now leaked into public domain.

— Martin Boon (@martinboon) November 19, 2017

Why? First of all let’s remember that the reason polls sometimes produce different results from one another, other than due to statistical noise, is that their methodologies differ. And if internal polls really did have such a superior methodology, why wouldn’t pollsters that conduct both internal and published polling, change the methods for their public polls – on which their reputations rest – to make them as accurate? Or as Jo Green, who ran the Labour press office under Ed Miliband, puts it:

Most of the “private polling” I’ve ever seen turned out to be wrong

— Jo Green (@jg_ccpress) November 19, 2017

Britain isn’t even like the US, where the vastly higher campaign budgets do sometimes allow party pollsters to do things differently. Yet even there, the evidence on accuracy is at best mixed. As Nate Silver wrote after the 2012 US election, when Mitt Romney’s internals proved a bit too optimistic, we shouldn’t assume that information is valuable simply because it’s private or proprietary. It might simply be something that someone wants the media and public to hear.

Of course, the Tory case is unusual in that the private polling reportedly shows something worse for the Conservatives than do the public polls. But the point still stands – polling leaks have a strong track record of being in some way beneficial to the person behind the leak.

And irrespective of what internal polling shows, for Labour actually to be 12 points ahead would require public polls to be wrong by a net 10 points or so – more than they’ve ever been at a general election (top of the hall of shame is 1992, when final polls were off in the opposite direction by an average of 9 points).

Though that’s possible, the excitement around the idea that Labour has a huge lead probably owes more to such a scenario fitting both the “government in trouble” narrative, and the social media myth that there is widespread rigging of published polls, than it actually being statistically likely.

But more to the point – and this isn’t always obvious – an internal pollster’s central objective isn’t to produce some topline methodology that beats everyone else’s numbers into the dust. Their job is to help their client win. That requires all sorts of other questions, and in reality the voting intention numbers often aren’t even all that important.

Private polls typically serve purposes such as tracking brand perception of the party, of other parties, and key individuals. Or message testing, often in conjuction with focus groups, and checking how well a message or news story is penetrating a particular audience.

Given how sensitive all of that information has the potential to be, parties tend to keep it fairly tightly controlled. It would be pretty odd for it to be circulating widely among Tory MPs, particularly in the present environment.

Campaigns also make use of analysis that’s rarely seen in public polling, such as grouping voters into segments (a bit like this) based on a variety of variables, and using those (rather than simple geography or demographics) as crossbreaks. And they tend to focus more on relative measurement – differences by voter type and changes over time – than on absolute levels.

The bottom line is that while the public polls could be a bit wrong, or even very wrong (in either direction), this claim is far from convincing.