The news that President Trump has tested positive for coronavirus has immediately prompted speculation around its potential affect on the US Presidential election. Since it always takes a while for new polls to be conducted, speculate is all anyone can really do in the meantime.

There is, of course, a precedent for a leader catching the bug – on 27th March Boris Johnson announced that he had tested positive for coronavirus. What effect did that have on British polling? Here’s a tweet from Carole Cadwalladr claiming that it led to a surge in support:

A reminder to all Americans that the net effect of our prime minister catching COVID-19 was that it prompted a surge of patriotic support. From which he emerged with renewed popularity. Which enabled him to tear up key functions of the state

— Carole Cadwalladr (@carolecadwalla) October 2, 2020

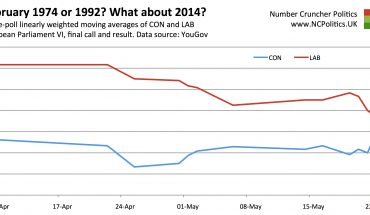

Now, it’s not absurd to draw that conclusion. Johnson and the Conservatives were doing extremely well in the polls shortly after his diagnosis, having been doing less well shortly beforehand. Here’s a chart featuring YouGov data:

Is this chart from YouGov then incorrect?https://t.co/mkfihA7tog pic.twitter.com/EeFgppxDEI

— Johan Farkas (@farkasjohan) October 2, 2020

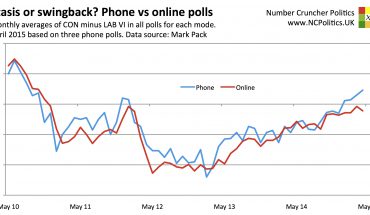

The problem is that “shortly before” and “immediately before” are not the same thing. And the circumstances in the early part of 2020 contribute to the difficulty in distinguishing between the two.

Firstly, it was only a few months after the UK general election, meaning that relatively little polling was being conducted – clients had used up their budgets on polling during the campaign (after an already busy 2019 in the runup to Brexit) and in any case people are just less interested straight after an election with a clear result.

Secondly, the amount of newsflow in the early stages of the pandemic complicates discerning the timing of movements in public opinion – even very large and rapid movements – if you don’t have sufficiently frequent data.

What actually appears to have happened is that support for both Johnson and his party increased gradually during the first half of March and then increased very sharply in the third week of March, as a rally round the flag took hold.

You can kind of see it from this Wikipedia chart of voting intention, although the dots (representing individual polls) aren’t adjusted for house effects, and the LOESS trendline probably uses a bit more alpha (the smoothing parameter) than you’d use if you were looking to pick up a rapid shift:

This is not what happened. Two separate polls (by us and Opinium) done BEFORE Johnson announced his positive test on 27th March put the Tories on 54% with a 26 point lead. We had him on 72% satisfaction. Neither that, nor his ICU admission, had a discernible effect on the polls. https://t.co/k1TRs2k2en pic.twitter.com/1K7YVwiKoL

— Matt Singh (@MattSingh_) October 2, 2020

It’s more helpful if we look at apples-to-apples comparisons using frequent data. Here’s YouGov’s weekly government approval tracker:

Useful tip for my intro to quant methods students: don’t claim the line on the graph went up when the line on the graph went down. https://t.co/fq1i83UIm7

— Rob Ford (@robfordmancs) October 2, 2020

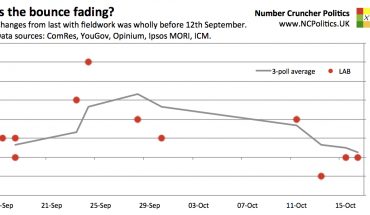

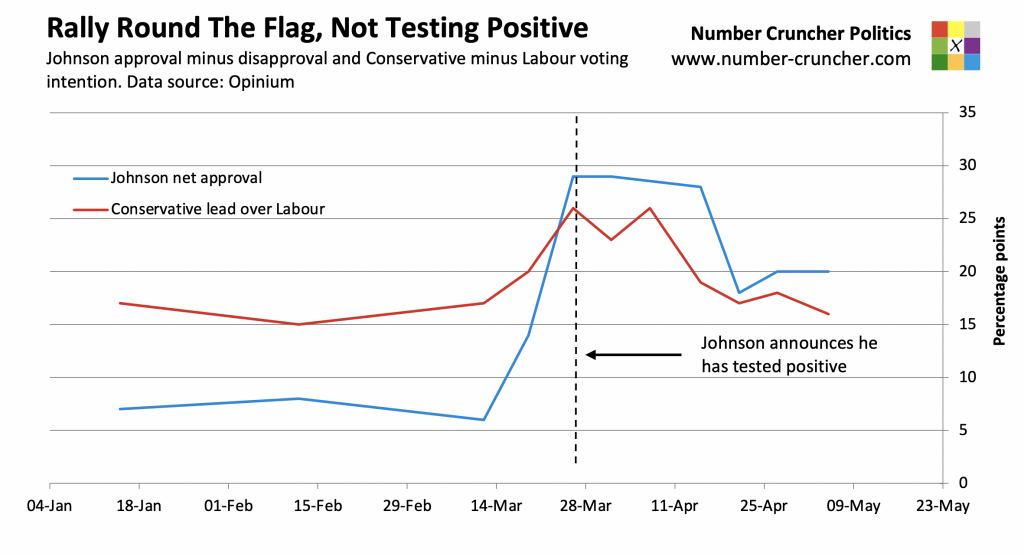

Opinium was also polling most weeks. Here’s a chart of its voting intention and Boris Johnson’s net approval numbers:

It’s likely that the absolute peak of Johnson’s popularity was immediately after his televised address on 23rd March, which introduced key “lockdown” measures. By coincidence, Number Cruncher was in the field at that exact moment for our Bloomberg poll. In the early stages, our fully-weighted interim numbers were approaching SIXTY per cent Conservative voting intention.

Although this faded back to “only” 54 per cent by the time we’d finished, this was still the biggest poll lead for a Tory government since the Falklands war in 1982, and entirely before Johnson announced on 27th March that he tested positive.

Now, it is probably true that Johnson and the Conservatives were polling so well at this point that it would have been very difficult to do much better. Had he/they been polling less well, there might have been a bounce. Or there might not. The point is that we’re now getting into counterfactuals rather than what actually happened and when.

And while it’s not absurd to draw the conclusions that some have drawn based on a glance at low-frequently charts, it’s equally clear that these conclusions are wrong – there was a surge, but before, not after, Johnson went into quarantine (and subsequently into hospital).

So what does this tell us about the US? Well, probably not much. A number of important factors are different, not least that we are talking about different systems of government, different levels of polarisation, different points in both the pandemic and the electoral cycle, one incumbent with (at the time) a massive poll lead and one with a poll deficit, and so on. There are quite a few reasons to warn against reading very much across from the UK experience to what might happen in the US.

But if we are going to talk about the UK, let’s get the facts straight. Johnson’s Corona bounce was from the rally-round-the flag, not from catching the virus himself.