On Thursday, Northern Ireland goes back the polls to try to elect a new government. I say "try to" because government formation may prove very difficult this time. Under the system of power sharing in use since the Good Friday Agreement, the largest unionist party and largest nationalist party (barring a monumental upset, those will be the Democratic Unionists and Sinn Fein respectively) jointly form the executive. Since very little has changed since the collapse of the previous Stormont government, hopes of a them actually succeeding in doing so are not high.

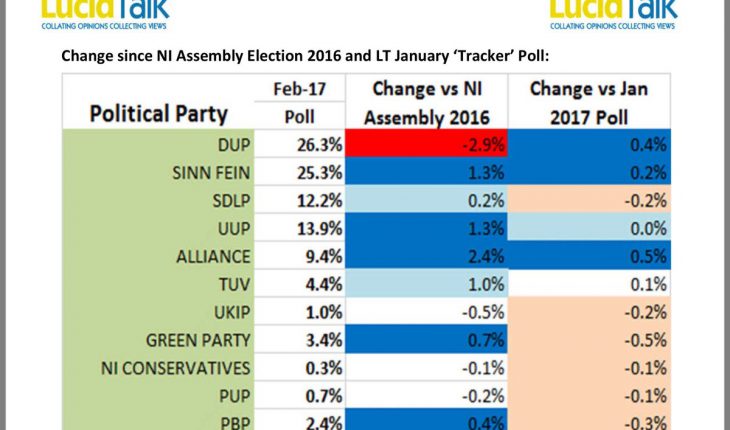

The electoral system is single transferable vote using the same 18 constituencies as Westminster elections, although there is an important change this time (see below). The final poll by LucidTalk found the following levels and changes of support:

Full details of the @LucidTalk NI Assembly pollhttps://t.co/xwagfZONXp pic.twitter.com/9jsWF9qvtT

— NumbrCrunchrPolitics (@NCPoliticsUK) February 28, 2017

Here are some things to watch for:

1 – Impact of the Renewable Heat Incentive affair

The odd circumstances (a green energy scheme gone wrong, when now First Minister Arlene Foster was the minister in charge, more background here) that lead to this election could also affect the election. Foster and the DUP have been on the back foot in polling and – according to those on the ground – on the doorstep too.

The drop in DUP support could even see them drop behind Sinn Fein in the popular vote – the former has lead in each of the polls, but well inside the margin of error.

2 – Impact of Brexit

There are a number of ways that Brexit could have an impact, from differential party support to differential turnout. But it might also lead to increased turnout overall. This is the first significant vote in the UK since the referendum, so it will be interesting to see if the higher-than-normal poll last June leads to an increase in a legislative election, particularly as turnout in Northern Ireland has historically been low.

3 – Unionism versus nationalism

The proportion of the electorate that is broadly unionist or broadly nationalist doesn’t change much in the short term (the last election was only 10 months ago) but incrementally over time with demographics. But electors and voters are not the same thing. All indications (including from the polling) are that the nationalist camp are a bit more enthusiastic about this election, which may lead to differential turnout and help their prospects.

4 – First preferences

There’s a rule of thumb known as the “LucidTalk rule”, that candidates hoping for a seat need – at a minimum – half a quota in the first round to have any real chance of being elected on lower preferences. Historically, many candidates have cleared this bar and still lost, but very few have missed it and still won a seat. Given the reduction in seats (and therefore rounds of counting), this rule of thumb may become even stricter.

5 – Cross-community exchanging of lower order preferences by moderates

This is where it gets really interesting. The LucidTalk polling has found evidence of greater-than-normal exchanging of lower preferences between supporters of the Ulster Unionists and the Social Democratic and Labour Party, rather along community lines. This could be decisive in later rounds, even though first preferences remain key.

Note that even on first preferences, the cross-community Alliance Party has been gaining somewhat. It may be helped by what was generally viewed a strong performance by its leader Naomi Long in Tuesday’s BBC debate.

6 – Effect of the reduction in seats

Stormont is being trimmed from 108 to 90 seats, or from 6 to 5 per constituency. That means that the quota (the number of votes needed to guarantee a seat) increases from one-seventh to one-sixth of the poll in each one. That will make things trickier for some of the smaller parties, who may find themselves with the short straw. But in some cases it could hurt the larger parties where they have narrowly won a third or even fourth seat out of six, but have little hope of winning the same number in a five-member constituency.

Another thing to remember is that as a result of the reduction, a party that wins the same number of seats as last time is winning an increased share of the seats, and one winning fewer seats isn’t necessarily losing out compared to the other parties. (Thankfully there are no boundary changes this time!)

7 – The skew

Although the voting system is proportional, it isn’t perfectly so. Some parties have more efficiently distributed votes than others, and in any case there’s the matter of lower preferences too. So the party that tops the popular vote in round one may not have the most seats by the end. If Sinn Fein and the DUP are tied on votes, the latter is thought likelier to have more seats.

8 – A very long count

Polls are open from 7am to 10pm as normal in the UK. But due to the complicated electoral system, there is no overnight counting and the ballot papers stay in their boxes until Friday morning. Verification begins at 8am, followed by the count, with about most of the seats declared on the Friday.

9 –What the parties do next

In theory, the parties have three weeks to form a government. Given that The DUP and Sinn Fein have incompatible red lines (not least that Sinn Fein will not work with Foster, but she has refused to stand down) the signs aren’t promising.

10 – Westminster

If – as is widely expected – they don’t, the ball is in the court of Northern Ireland Secretary James Brokenshire. Yet another election is one option, but there is no guarantee of a different outcome. So it may lead to a period of direct rule (suspension of devolution) until a solution can be found.