Ok that escalated quickly. In reference to an article by Nate Cohn in the New York Times, regarding the USC/LA Times poll (which has tended to show much better numbers for Donald Trump than everyone else), I tweeted this:

Interesting read, I'll be posting something on this later. In general, past vote weighting has made GB polls more accurate, not less… https://t.co/6MGaOLaclk

— Matt Singh (@MattSingh_) October 12, 2016

…which lead to a couple of voicemails from city traders asking if I thought the polls were all wrong, as in the UK last year. Well there’s no 6,000 word essay this time, but this poll does raise some interesting questions about methodology.

There are two main issues here – firstly the way the poll handles the now famous (but unidentified) 19-year-old African-American Trump supporter in Illinois, and secondly the use of past vote weighting. On the first point, it’s pretty clear to me that weighting the living daylights out of tiny cells (subsets of respondents) is not best way to weight, for all the reasons that Nate Cohn gives. It’s often helpful to “interlock” weights where possible (for example, age and gender, so that each age group is gender balanced) but only if the sample contains enough responses in each demographic to do it safely.

If it doesn’t, you can end up with a handful of people getting a huge weight. This has the same effect as reducing the size of the sample, so that the effective margin of error increases (technical terms, the weighting efficiency drops) which is problematic in itself. Moreover, if some (or even one) of the heavily-upweighted respondents is wildly atypical of their demographic, they can skew the poll. So it’s best not to work the sample so hard.

As a fallback, it’s also common practice “cap” the weights, that is to limit the weight any one person can carry.

The second point is more controversial. Unusually for polls in the US, the USC/LAT poll uses past vote weighting, in other words, asking people how they voted in 2012 and comparing it to the election result (and ensuring that the two match). A representative sample should, of course, contain the right proportions of Romney and Obama voters and people that didn’t vote. The problem is what’s known as false recall – people misremembering how they voted four years ago, if they did so at all.

Among those that said they voted, recalled 2012 votes generally show Obama winning by considerably more than his actual four-point margin. But is that because people are misremembering what they did, or because polls have too many Obama voters?

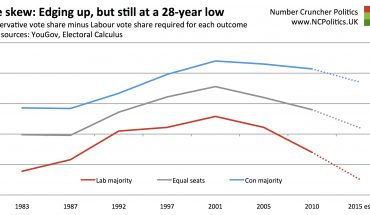

This is of particular interest to those of us that follow elections in UK, where (unusually) past vote weighting is commonplace, with all regular pollsters besides Ipsos MORI either directly or indirectly weighting their samples to the result of a previous vote (usually the most recent Westminster election). The practice was introduced by ICM back in the 1990s after the industry-wide miss in 1992, one cause of which was undersampling Conservatives. It seems to have improved polling accuracy in most British elections since (though this is contested), but may also have concealed other problems that only came to light last year, when the polls missed once again.

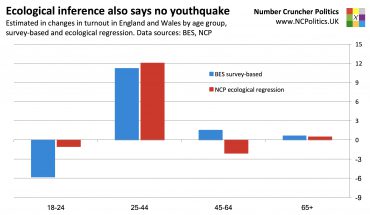

If people misremembered randomly, there wouldn’t be a significant problem with past vote weighting, because the errors would be in opposite directions would cancel out. The problem is that they don’t. One common theme everywhere is that people tend to recall voting when they didn’t, just as they overestimate their own probability of voting beforehand.

Americans also seem to over-report voting for the winner, which isn’t normally the case in the UK, (at least, not in a big way) though it makes sense that this would differ between a parliamentary and presidential system.

There’s also third-party bias, a much bigger issue in the UK than in the US, because the two main British parties generally get no more than 70% of the vote. Curiously the bias seems to run in opposite directions in each country – British voters have tended to underreport third-party voting, Americans seem to overreport it.

So there are significant biases involved. But is that really enough to explain the sort of recalled 2012 numbers we’ve been seeing, such as Obama beating Romney by upwards of 15 points? This seems like a lot of false recall, but is it wrong?

One clue comes from polls that use online panels, where people that were in the panel four years ago can be recontacted, and the results compared with the answers they gave at the time. The past vote weighting can then use the election result, but combined with an adjustment for expected recall error.

If we look at the past vote numbers that these online polls are getting, we find much smaller margins of Obama+7 or so, which may point towards sampling issues in other polls, rather than false recall. But before assuming that the polls are skewed, note that the toplines from these types of polls are showing similar numbers to most of the others.

The reason is likely to be that the excess Obama 2012 voters aren’t typical of all people that voted that way. Quite often when additional weights are added to a poll correctly, so ensuring that the sample still meets all the weighting targets for other things like demographics (rather than the “unskewing” nonsense that became popular four years ago) the effect is often surprisingly small. In fact when the Upshot did this, it only made a point or two’s difference, suggesting that the impact of the possible skew is considerably smaller than it looks.

And that is of course pretty small, compared to the many other things that could be throwing polls off, in either direction. In fact 2016 is a very tough year for pollsters anyway, but I’ll return to that another time.

So while the odd-looking recalled past votes make for an interesting debate about polling methodology, they are not a smoking gun.