Ever since the clock struck ten on the 7th of May, one question has dominated discussion of opinion polling in Britain – how did the polls get it so wrong that an apparent photo finish was, in reality, a Conservative outright majority, an outcome to which many forecasters has ascribed a negligible probability?

Quite often spotting a statistical pattern is easier than explaining it. Sometimes, spotting the pattern before the fact is harder even than explaining it afterwards. But based on the election results, weeks of earlier analysis and finally on Friday, the results of the British Election Study (BES) probability survey, I’m able to present my assessment of what happened.

Tom Clark, breaking the BES story in the Guardian, wrote that the polls may have failed “because those interviewed were not selected randomly”.

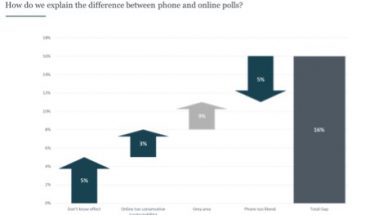

That would be my interpretation of the BES data, too. But as is so often case, things aren’t as straightforward as they appear. If online and modern telephone samples were inherently useless, the kind of polling failure that we saw in May’s general election would be happening left, right and centre. It’s true that polls have generally underestimated the Conservatives and overestimated Labour (though not as much as this year, besides 1992 and 1970). And it’s also true that in the very recent past there has been a spate of incidents around the world of parties on the right (and usually the centre-right) outperforming their polling.

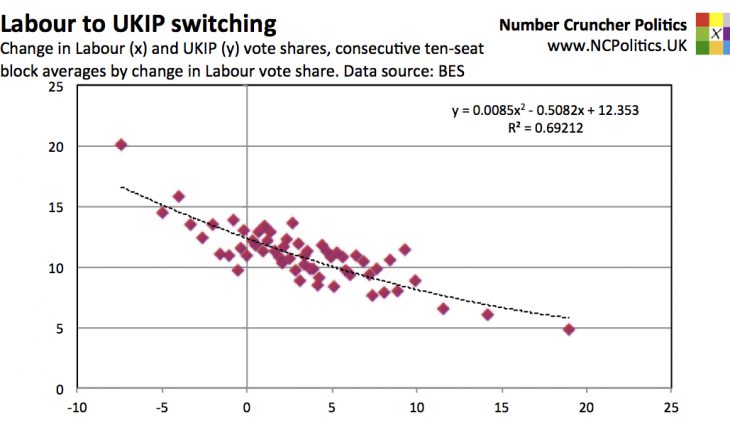

But the same companies using the same methods, sometimes even within the same polls got a number of things right. They were spot on in Scotland and reasonably close in London. They got the Lib Dem and Green vote shares about right. Despite all the (understandable) concerns about polling for UKIP – given that the party had increased its vote share many times over since 2010 – and the huge variations between pollsters, the industry average was just 0.1 points from the result. And at the Scottish referendum, despite all of the noise about one poll that – almost certainly due to nothing more than statistical noise – showed Yes ahead, YouGov’s final on-the-day polling was within a point of the outcome.

The above isn’t a defence of what happened in May – the polls were completely wrong on the one number that mattered more than anything. But the point is that it wasn’t normal. This was an atypical event, even though none of the now widely-discussed risks to polling accuracy are particularly new or novel. Internet polls are statistical models based on self-selecting panels rather than random samples, but that has always been the case. Telephone poll response rates have become horrendously low, but as part of a gradual, long-term trend – they didn’t fall off a cliff overnight. Turnout in British elections is low by historical and international standards, but it has been for some time – this year’s 66% was the highest since 1997. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that something specific went very wrong.

(Continued, please navigate using numbered tabs…)