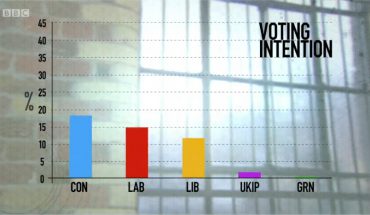

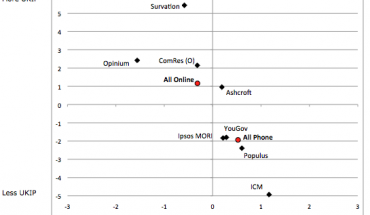

The Conservatives have retaken the lead with YouGov but remain some way from where they need to be to win a majority. Their conference ended in a wave of patriotism, optimism and “we know this is a huge ask, but we’re going to give this everything”-ism. So how big a task is it?

I’m going to go into the 2015 electoral maths in more detail in future articles, but in short: While it would be possible, under certain permutations, for the Tories to win without getting more votes than they did last time, winning becomes a lot more straightforward if they can actually get more crosses in boxes. Increasing the popular vote can be done by getting your vote out more effectively – John Major got more votes in 1992 than anyone else before or since, on a higher turnout than in any of Margaret Thatcher’s three victories. But his share of the vote was slightly lower.

Increasing your share of the vote while in government is an extremely rare achievement, though not entirely unprecedented. I don’t have reliable vote share estimates from before the Great Reform Act (and nor does Wikipedia) but here are the six such examples since 1832:

A few things to note:

- October 1974 and December 1910 were both after a very short term, with another election having taken place earlier that year.

- 1955 and 1868 came after at least one change of Prime Minister between elections and after a parliament of around 3½ years… Whether that qualifies as a ‘full’ term or not is debatable, but they certainly aren’t ‘reruns’ as in the above cases.

- 1857 is an oddball, because the Conservatives won in 1852 with a wafer-thin majority, only to be brought down by a Peelite rebellion five months later. John Russel’s Whigs then formed a government (without a further election) until dissolution under Palmerston in 1857 (after more than four years in office). As such, even though the Whigs actually lost the prior election, I’ve included 1857 because they were in power for nearly all of the intervening parliament.

- According to some sources, Andrew Bonar Law technically increased the Conservative vote share by 0.1% in 1922 (as compared with the combined Conservative and Coalition Conservative share from 1918) but only if you ignore the fact that Irish votes were no longer included. As such, I’ve discarded this election.

The khaki election of 1900 is the only example that is directly comparable to what the Tories are trying to do now – the same Prime Minster with an increased vote share, after a five-year term. Even that has a bit of an asterisk next to it, as the Liberals contested around 10% fewer seats than they had five years earlier (though it isn’t clear how by much that reduced their popular vote).

So while the Conservatives’ intended outcome wouldn’t be unprecedented, there are only four examples following a term longer than a year, only two after a five-year term and only one (possibly) with the same Prime Minister from election to election. All of this lends support to the broad consensus that the Tories have a mountain to climb to win a majority in 2015.

But there is one more thing to add. As per another consensus (that many things are different this time) historical comparisons might be less relevant in 2015. That is a whole other debate, but one thing to bear in mind is that, prior to 1974, there were only six occasions in electoral history where a party other than the two largest won more than 10% of the vote, and five of those were during the Liberal-Labour crossover era between the wars. But only once (in the parliament following the 1929 election) has a third party collapsed in the way the Lib Dems have in opinion polling since 2010. Only a minority of 2010 Lib Dems are blue at the moment, fewer than the number of voters that the Conservatives have lost to UKIP, but this the kind of way that history might not necessarily be a foolproof guide to the future this time.

And despite completely, totally different circumstances, the above holds one tantalising omen for the blues – in that election in 1929, the Conservatives polled more votes than Labour but failed to win, the Liberals secured 23.6% of the vote and just under 60 seats, before falling into single digits, and the bulk of their lost votes went to the Tories, who won the next election. In 2010, the Conservatives polled more votes than Labour but failed to win, the Lib Dems secured 23.6% of the mainland vote and just under 60 seats, before falling into single digits. If David Cameron can somehow make history repeat itself, he might just stand atop that mountain.