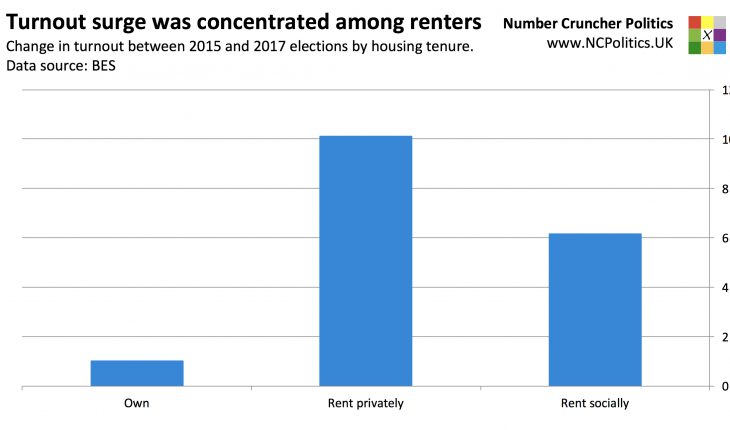

Recently I wrote for Bloomberg View with some analysis of the 2017 election result and the importance of housing. The youthquake was in fact a rentquake, and the swing to Labour was entirely accounted for (in the statistical sense) by housing. Quite a few people asked, in private and in public, whether this correlation was spurious. After all, renters tend to be younger, the crucial 25-44 age bracket is heavily Remain, and so on.

In particular, Stephen Bush wrote an interesting piece, asking similar questions, but first discussing the distributional effect (in other words, how vote totals translate into seat totals) of liberal/left middle class voters being priced out of urban areas and moving into more competitive areas. That may be the case, and it’s an interesting topic, but at this stage I’m purely talking about the popular vote. Stephen also wrote:

“Increasingly I think the turn to Labour among renters might be a bit of a false positive: many people renting turned towards Labour, but that they were renting is sort of a secondary factor. More important vote-drivers include: their concern over cuts to schools and hospitals, anger about Brexit and the government’s broader turn towards the socially illiberal, in addition to the pressure on wages caused by the economy being in a slightly worse state in 2017 than in 2015, when the fall in the petrol price made people feel more affluent.”

It’s right to ask these sorts of questions. Naturally I’d already given this some thought (particularly in relation to Brexit) but since writing the Bloomberg piece, I’ve crunched the numbers some more. And I still don’t think it’s a false positive.

Using the data from the 2017 BES probability survey, I estimated logistic regressions for the Labour and Conservative 2017 vote probabilities, controlling for 2015 vote in order to isolate the switching. Even after additionally controlling for age, gender, region, education, EU referendum vote, various measures of social liberalism, views of their personal finances, the economy, NHS, schools and tuition fees, a respondent’s housing tenure was still a statistically significant predictor for both main parties.

In most of the model formulations, being a renter rather than a homeowner increased the probability of voting Labour by about 5 percentage points and reduced the probability of voting Conservative by the same amount, equivalent to a 5 per cent swing among renters, and suggesting that only a fraction of the optical 6.5 per cent swing within that group can be explained by correlation with other factors.

That’s not to say that other things aren’t still relevant. It’s quite possible that austerity fatigue, Brexit or something else helps explain when the rentquake happened. I just don’t think we can easily dismiss housing tenure as an explanation of who changed their vote, or voted for the first time. I’m not sure whether that makes it a primary or secondary factor – my analysis is that housing is cross-sectional (the “who” and the “where”) and other factors are longitudinal (the “when”).

Why else might the rentquake have happened in 2017 but not 2015? There are a few possibilities. Renting might not have got much worse in absolute terms, but the widening gap between house prices and wages has put home ownership further out of reach for many people.

And I’m not sure whether Labour actively targeted renters, but it could be that its campaign – widely hailed as a success – hit home with renters, including many who hadn’t previously voted Labour (or at all). It’s also possible that voters willing to give David Cameron the benefit of the doubt (or simply stay at home) in 2015 after a full term, weren’t so generous to Theresa May in a snap election. This is certainly an area for further work.

Those of you that follow me closely will know how I often point out that things are often more complicated than they seem. It’s just about conceivable that this turns out to be another one of those. But looking at the data, it does, genuinely, look like a housing effect.

Is the rentquake analysis a spurious correlation?

|

19th March 2018 |