When by-elections are hotly anticipated it seems that they either end up being – from a neutral perspective – an all-time classic (e.g. Richmond Park) or total anticlimax (e.g. Oldham West & Royton). The Copeland by-election is certainly anticipated, partly because of the possibility of a change of party and partly because it's been flagged well in advance (Jamie Reed hasn't even taken the Chiltern Hundreds yet).

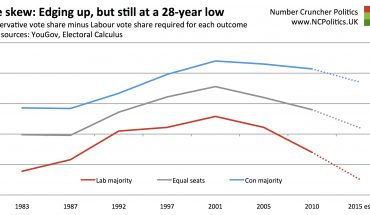

As I mentioned in my preliminary look at the contest, governing parties face a significant drag in by-elections and almost never gain seats – when they have (in Great Britain since 1945), it has always been in either strange circumstances or where the majority was far smaller than the 6.5 points that Labour achieved in 2015, and usually both.

But what, historically, might we expect? If Copeland simply followed normal historical by-election patterns, taking no account of the state of the national polls, the Labour majority would increase substantially to about 29 points, or an 11% swing in their favour:

But the national polls do matter, because governments performing well nationally also tend to do a bit better in by-elections, even though the relationship between them isn’t one-for-one.

Using a more sophisticated model that takes current polling performance into account, as well as the stage we’re at in the electoral cycle and the government we’re looking at is Labour or Conservative does make a difference, but not a huge one – Labour still wins by about 23 points on an 8.5% swing:

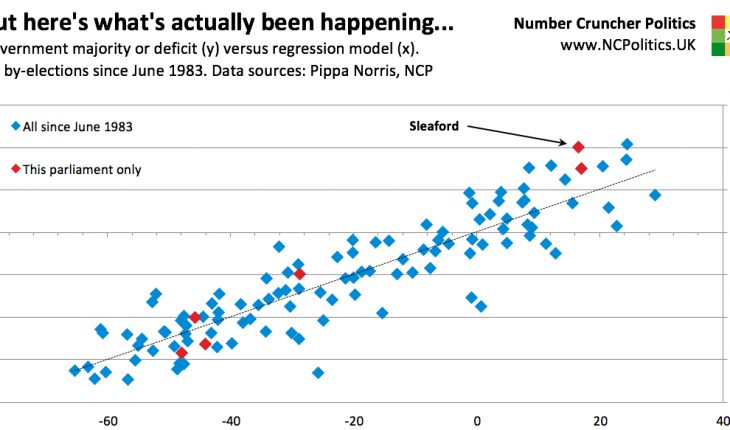

This tells you what to expect on paper. But what’s actually been happening recently is rather better for the Tories. Below is the same chart as the one above, but with the results in the current term in red. All the of the recent ones (which also happen to be those outside of safe Labour seats) have seen a better Tory performance than the model would have predicted.

If the Conservative performance at the Copeland by-election (or to use the technical term, the residual – basically how far the red diamond is from the dotted line) is the same as its average across by-elections in this parliament, then they do even better, but even then there would still be a swing to Labour and an increased majority of about 18 points:

BUT – at the last by-election at Sleaford and North Hykeham, which wasn’t just the most recent but also the only contested by-election since the EU referendum with a similar Leave vote to Copeland, the Conservative result wasn’t so much an outperformance as a demolition job. The Tory majority should have been reduced to 16.5 points, but it increased to 40, their strongest defence since 1982.

If you extrapolate the residual from Sleaford (+23.5) then the likeliest outcome in Copeland would require recounts.

So given the enormous difference, which set of numbers is right? What matters is why the Tories did so well in Sleaford. Was it because it was a safe Tory seat, or because it was a strongly Leave seat? Or was it part of a trend? (The residuals have been getting bigger). If it’s the second or third of these, then Labour is probably in trouble in this seat, if it’s the first, they’re probably not.

Since we can’t rule out the first possibility, Labour’s chances are probably a bit better than most people are assuming. Here’s a sort of “ready reckoner”:

| If Copeland by-election is like… | Then the theoretical likeliest result would be… | Which is swing of… |

| Average by-elections since 1983, ignoring national polls | Lab majority 29 pts | 11% from CON to LAB |

| All by-elections since 1983 |

Lab majority 23 pts | 8.5% from CON to LAB |

| By-elections in this parliament only | Lab majority 18 pts | 5.5% from CON to LAB |

| The last by-election at Sleaford & North Hykeham | A recount | 3.5% from LAB to CON |

Of course, even if we knew which of these scenarios we’re in, they are just the theoretical likeliest outcomes, within a wide range. There is always plenty of noise, and possibly other factors – local issues, short-term politics and the length of the campaign – to keep in mind.

The bookies and markets have the Tories as narrow favourites, but really the picture is that it could go either way – and I’m not going to argue with that.