Today the Scottish Boundary Commission published its initial proposals for the new Westminster boundaries. As I did for the English and Welsh boundaries last month, this is an analysis of the impact of the review on Scotland’s Westminster seats.

As part of the UK-wide reduction in the overall number of seats, Scotland loses 6 seats and now has 53. Proportionately, that’s slightly more seats than England, due to English seats having expanded more since the last review. (Scotland still has more MPs relative to its electorate, or alternatively its MPs have about a thousand fewer constituents, because the Northern and Western Isles seats are allowed to be much smaller that the normal minimum size).

Before going through the notional results, let’s be clear about what notional results are. They are the results of the 2015 election if the same votes had been cast on the proposed new boundaries. They are not necessarily what the results might have been if the election had actually been fought on the new boundaries. This matters, because if voters had been in different constituencies, they may have voted differently, for tactical reasons, or due to incumbency effects.

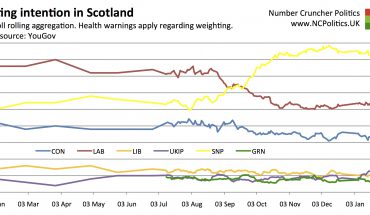

And they are certainly not a prediction of the next election – votes have moved around since May 2015, and will move around some more, so bear that in mind when thinking about small majorities in notional seats. Also, some seats have changed hands due to their MPs having the whip withdrawn – this too is treated as a change since the last election.

Also, these numbers, like any others you’ll see, are estimates. In Britain there is no breakdown of general election voting at any level lower than constituency, so if we want to know which bits of each constituency voted which way, we need to infer that from other data. The stock approach is to use the patterns of local election results, as I do here, but geodemographic modelling is probably better.

Down south the two methods get extremely similar results, but in Scotland they might not. The last local elections in Scotland were in 2012. That was also the case in Wales and many parts of England, but Scotland has seen enormous (and crucially, very uneven) swings in voting behaviour since then. So when we get the next batch of locals next May, some results might look a bit different.

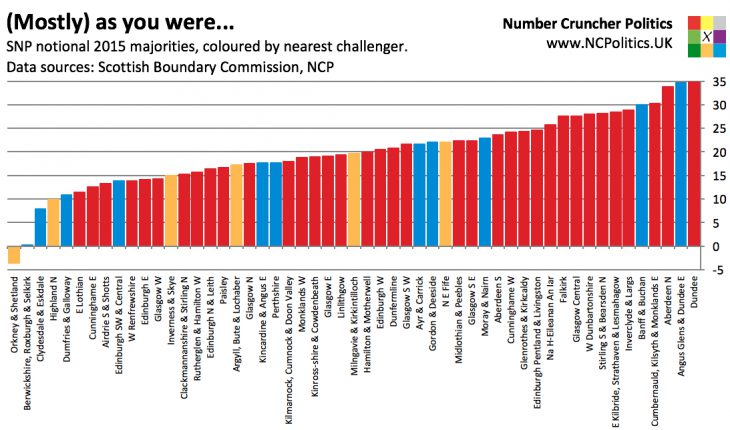

If we take the 2015 votes and the new boundaries, we get a notional result like this:

New Scottish boundaries – notional 2015 result is:

SNP 52 (-4)

LD 1 (=)

CON 0 (-1)

LAB 0 (-1)(Though one seat would be extremely close) pic.twitter.com/TEknATCqNT

— NumbrCrunchrPolitics (@NCPoliticsUK) October 20, 2016

The bulk of seat reduction inevitably comes from the SNP, since they virtually swept the board last year. But rather than 56 out of 59, they now notionally have 52 out of 53, so proportionately they are big winners. They do however have to decide which four MPs would have no seat to contest – potentially a bigger headache for them than for other parties, because 48 of the current 54 MPs with the whip were newly elected in 2015, so presumably there aren’t too many (voluntary) retirements on the cards.

Notionally, the SNP now holds every seat on the Scottish mainland, and the Western Isles for good measure. The biggest SNP majority is in the new Dundee seat (35 points). Almost half (25) of the new seats have an SNP majority of 20 points or more.

The Lib Dems, now notionally Scotland’s second party at Westminster, retain their Orkney and Shetland seat as it is one of the four protected island constituencies in the UK, so isn’t subject to the review. Therefore its its notional 2015 result is the same as the actual result. The party is second in a further five seats, with its best starting position in Highland North, where a 5% swing from the SNP would gain what is set to be the largest seat in the UK by area (at just under the legal limit of 13,000 square kilometres).

Labour-held Edinburgh South gets split into Edinburgh Southwest & Central and Edinburgh East, and there is no notionally Labour-held seat in Edinburgh (or anywhere else in Scotland). Labour is notionally about 14 to 15 points behind the SNP in each of these two new seats, although in Edinburgh Southwest and Central the party is narrowly third behind the Conservatives.

Looking at the new Labour-SNP battleground, the pattern that keeps popping up everywhere is that where Labour is second, the SNP has an above-average vote share (and in every case, a double-digit percentage majority). There are a handful of seats where the SNP vote share is projected to be in the low 40s, where Labour could theoretically challenge given enough Unionist tactical votes from Tories (and in Edinburgh West, Lib Dems as well). Their problem is that with Labour having gone backwards since 2015, the Tories are arguably better placed in all of that type of seat, so the chances of that kind of strategy working (for now, at least) don’t seem that great.

The Conservatives don’t do as well on these boundaries as on the “old” new boundaries. The old Dumfries proposal had a bigger Tory majority than their current Dumfrieshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale constituency, whereas the rough equivalent in the latest proposals, Clydesdale and Eskdale, would have had an SNP majority of about 8 percent. Neighbouring Berwickshire, Roxburgh and Selkirk is little changed, and remains very close indeed. I’m awarding it to the SNP after a couple of recounts, but given their low vote share in the seat, the nationalists would do well to hold on to it next time.

In total the Tories are second in 11 Scottish seats. This is perhaps the most interesting battleground because the swings since 2015, both in Westminster polling and the Holyrood result, have pointed towards these constituencies becoming more marginal, not less. On these numbers, the Tories’ three prime targets across the border should all be winnable. After that comes the aforementioned Edinburgh Southwest and Central, with its three-way split. Then come a set of mostly rural, mostly northeastern seats that would need swings of 9% and upwards to turn blue. Those sorts of swings were evidence in some of the “Tartan Tory” areas at Holyrood, but whether the Conservatives can repeat them in a Westminster election remains to be seen.