By-elections. Rarely if ever do you hear so many questionable interpretations of a result from so many people. I’m going to write a sort of more generalised reference piece for by-elections, but for now, lets cut through the noise and analyse the signal from Thursday.

The first of the two contests to declare was Batley and Spen, where Tracy Brabin was elected elected to succeed Jo Cox following her tragic murder in June. Because the seat was only contested by a handful of mostly far right parties, all of which lost their deposits, it’s pretty much impossible to read anything into the results.

But for the record, records were broken. Labour’s majority of 81 percentage points was the largest winning margin at any post-war by-election in Great Britain, according to Pippa Norris’s database. The share of 85.8% was the highest since Abertillery in 1950 and the second highest ever. Unfortunately, the very low poll (25.8%) represented the 7th lowest turnout, as supporters of the other main parties mostly stayed away. But Labour took so many of the votes that were cast that its 17,506 votes weren’t that much below the total that Jo Cox polled in 2015, suggesting that Labour voters did turn out in force.

In Witney, the result was as follows:

#WitneyByElection result:

CON 45.1 (-15.1)

LD 30.2 (+23.5)

LAB 15.0 (-2.2)

GRN 3.5 (-1.5)

UKIP 3.5 (-5.6)19.3% swing from CON to LD

— NumbrCrunchrPolitics (@NCPoliticsUK) October 21, 2016

That swing of 19.3% was the biggest for the Lib Dems against the Conservatives since Winchester in 1997. That’s partly because for almost the entire time since then, the two parties were either in opposition together or in government together, but it’s a long time nevertheless.

But how did each party do? Firstly the Conservatives: there are few certainties in by-elections, but one thing you can pretty much bank on is that governments drop back, given that it’s happened 96% of the time since 1983. It’s pretty much a given. The Tories were down 15 points, which is very close to the average for government defences since 1983 (-16pts). This effect looks even bigger if, as journalists like to, you talk in terms of votes rather than percentages. With turnout dropping from 73% to 47% (which is slightly below average for a by-election in a Tory seat), the majority of 25,000 would have been “slashed” to about 15,000 even before you take the almost inevitable drop in governing party vote share into account.

But might they have expected to do better than “par”, given that their national polling continues to defy gravity? Perhaps, but probably not, for a few reasons. First of all, the comparison is with 2015, when David Cameron was standing. Prime Ministers (and other party leaders) have a history of outperforming their party in their own seats, so the unwinding of that bonus (over and above normal incumbency) needs to be considered. Personal votes are often exaggerated, but they’re not zero. Remember too, that the Tories have a pretty horrendous record in by-election defences while in government, this being only their second such success since Richmond (Yorkshire) in 1989, so that needs to factored into expectations.

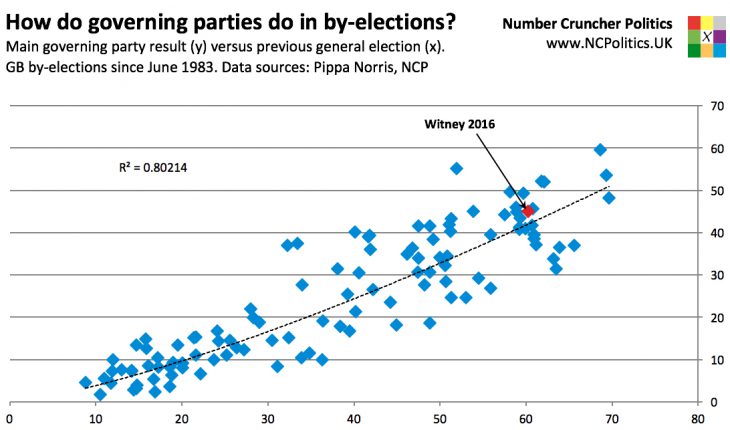

Moreover, -16 isn’t necessarily the right comparison, because in very safe seats, governments tend to do even worse, largely because they have more vote share to lose in the first place. As the chart below shows, the relationship isn’t parallel – a government defending a vote share of 60% on average would get about 41% – a bigger drop than actually occurred. There’s also a huge amount standard error around the fit, so unless the Conservative performance were wildly better or worse than this, attempts to spin it either way (including the idea that it represents some kind of Brexit backlash) are on factually shaky ground.

Taking everything into account, the Tory performance wasn’t that good and it wasn’t that bad. Sorry, but sometimes the truth can be dull.

How about the Lib Dems? They are clearly happy about this result – they threw the kitchen sink at the Witney by-election and it worked – with a 23.4 point increase in vote share. In fact if this by-election been polled, the Lib Dems may have been able to squeeze the Labour vote harder than they did. Votes tend to coalesce around the main contenders in a by-election – usually it is obvious from the previous general election result who those contenders are, but since the Lib Dems came fourth last time behind Labour and UKIP, it might not have been obvious to everyone. In particular, Labour voters might have been reluctant to vote tactically for a party that finished lower than theirs last time.

The less positive interpretation for the Lib Dems is that with the Tories losing vote share and everyone else being squeezed, that vote share had to go somewhere, and in this type of seat the Lib Dems were that somewhere. So although it confirms that a post-coalition rehabilitation is underway, the result itself isn’t earth-shattering.

But it’s certainly a reward for the Lib Dems’ patience – this is the first time since the last election that this type of seat has been contested – and it may lead to them getting a bit more exposure. A by-election in a Tory seat with a smaller majority would certainly be interesting.

Likewise, Labour coming 3rd with a reduced vote share isn’t a surprise in this seat. By-elections are generally two-horse races and other parties can get squeezed (15% is actually a bit above average for a 3rd placed party). And while oppositions can be expected to gain vote share in seats that they hold (as all previous by-elections this parliament have been) or where they’re the likeliest challenger to the governing party, that wasn’t the case here.

The Greens and UKIP also got squeezed (and lost their deposits) for the same reason.

So as tempting as it is to draw conclusions, Witney did just go pretty much to the form book.