The dust may have settled since the Ashcroft polls (his next instalment is due on the 4th of March) but there is still plenty to analyse. The overall Scottish Westminster picture shows very little change over the last few weeks, with the ten-poll aggregation showing figures of SNP 42 (-2) CON 17 (-2) LAB 27 (=) LIB 6 (-1) UKIP 4 (=) GRN 4 (+1). The electionforecast weighted model shows SNP 44 (+1) CON 12 (=) LAB 31 (=) LIB 6 (-1) UKIP 4 (+2) GRN 3 (=) (The changes don’t net off due to rounding). We also had a poll from Survation:

Survation (Scotland Westminster):

SNP 45 (-1)

CON 15 (+1)

LAB 28 (+2)

LIB 5 (-2)— NumbrCrunchrPolitics (@NCPoliticsUK) February 18, 2015

GRN 3 (=)

Survation (Scotland, best PM):

Cameron 23

Miliband 19

Clegg 5

Farage 6Broadly backs up what Ipsos-MORI found…

— NumbrCrunchrPolitics (@NCPoliticsUK) February 18, 2015

So some signs of a slight moderation in the SNP’s lead over Labour, but it remains substantial. The apparent upturn in the Conservative vote share may have been a blip, Survation show them gaining a point, but their vote share remains close to the 16.7% they polled in 2010. The other parties, including the Lib Dems, are a long way behind (more on the Tories and Lib Dems in a moment).

Following the Ashcroft polls, I did some analysis of what the Labour-held seats that he polled told us about those that he didn’t poll. To recap, the distribution of votes that Lord Ashcroft finds approaches a best-case scenario for the SNP – the swings are biggest in the seats where they need to be, but likely to be big enough to capture seats where they are starting off less far behind. On current vote shares, Labour need their 2010 voters in “no” areas to be substantially different to those in “yes” areas (which is, of course, possible) but as I said before, the national yes/no dispersion wasn’t that big.

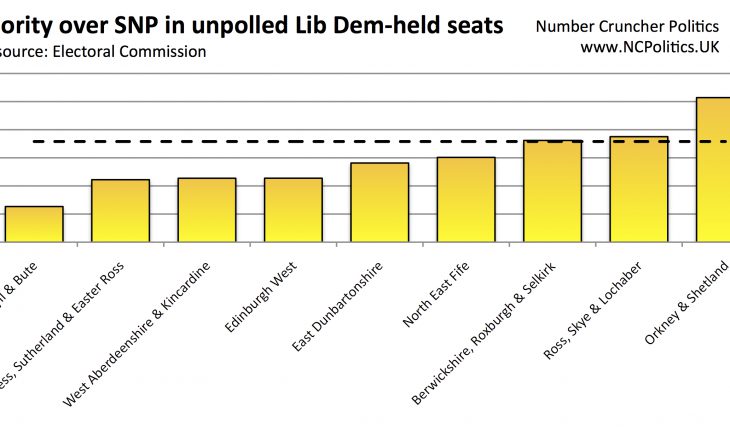

I thought it would be helpful to repeat this analysis for Lib Dem-held seats. Based on 2010 turnout and a 6% vote share across Scotland, the Lib Dems can expect to lose 318k votes in total. The first round of Ashcroft polling shows 62k of losses in those 16 seats, leaving 256k (or 13.8%) in the other 43. In half of those, that’s more than they polled in 2010. If we assume a lower bound of 2% in the seats the 34 of those 43 that they don’t hold, they would lose 192k votes in those seats, leaving about 64k (17.9%) to lose in the 9 seats they hold that have not yet been polled by Lord Ashcroft.

In both Lib Dem-held seats that were in the first wave of Ashcroft polling, the SNP vote increased by more than the Lib Dem vote fell. Even if it rose only by the same amount, a 17.9% swing would unseat all but three Scottish Lib Dem MPs, and leave Charles Kennedy perilously close in Ross, Skye & Lochaber. Alistair Carmichael should be safe in Orkney & Shetland in any event – it’s the safest Lib Dem seat in the whole of the UK.

That leaves the traditionally liberal Berwickshire, Roxburgh and Selkirk, successor to the seat held by David Steel from 1965 to 1997. Given the “no” landslide in the Borders, Michael Moore might well hold off the SNP, but his 2010 majority of 11.6 points was over the Conservatives – this seat had the second highest Tory vote share in Scotland in 2010, and the equivalent Holyrood seat is blue.

What about the Scots Tories elsewhere? Their vote share appears to be little changed from 2010, so David Mundell, their one MP for Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale & Tweeddale (where the SNP came fourth with just 10.8% in 2010) ought to be back. There are other seats where they could be in the hunt if the cards fall right, but they could find themselves in second place behind the SNP in many more constituencies. How would that prospect affect voting dynamics? I’ll address tactical voting in a future post.

I’m not aware of any forthcoming Scottish polls, although the Lib Dem private constituency polling expected to be released this week could include Scottish seats. Otherwise the next event should be Lord Ashcroft’s batch of constituency polls, to be released a week on Wednesday.