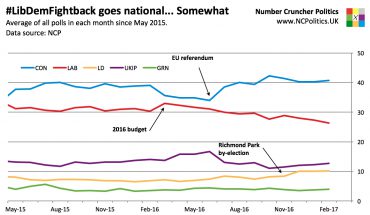

The pollsters are putting Lib Dems on everything from 5 to 11 per cent – what explains the difference?

This article first appeared on May2015, the New Statesman’s election site.

November has thus far seen considerable variation in the polling fortunes of the Liberal Democrats.

Their standing has veered from 11 per cent with ICM and 10 per cent with Ashcroft down to 6 per cent with YouGov and Survation and a twenty-four year low of 5 per cent with Opinium, while the May2015 average stood at 7.7 per cent shortly thereafter. What explains the differences?

All polls are subject to sampling error – the statistical variation that the same pollster would encounter between different random samples of the same population. But for a party polling 7.7 per cent, a sample of 1,000 has a margin of error of just ±1.65 points – all of these polls diverge from the average by more than that.

In most cases, this divergence can be attributed to “house effects”, the difference in the results that two pollsters would obtain from the same sample, resulting from differences in the methodologies, and specifically the way they weight their samples. The key difference in this case is the treatment of those who say they would vote, but don’t know or refuse to say who for.

YouGov excludes them altogether and reports only those who state a voting intention. Since those that “don’t know” include a disproportionate number of 2010 Lib Dem voters, this depresses the YouGov figures relative to pollsters that make some allowance for them.

Spiral of silence

ICM, by contrast, uses the composition of those that don’t know or won’t say to adjust their numbers for what is known as the spiral of silence. This technique was one it pioneered in the 1990s, following the industry-wide debacle at the 1992 election, when polls were about 9 points wrong on average.

Subsequent investigations revealed that many “don’t know” respondents had actually voted Conservative in the prior election. To counteract these “shy Tories”, ICM now reallocates 50 per cent of those not stating a voting intention to the party they voted for in 2010.

Recent ICM surveys have had a significant proportion of don’t know/refused among 2010 Lib Dem voters (e.g. 34 per cent in this recent one), magnifying the adjustment to around 3 points. While this is just one of many methodological differences (ICM is by telephone, YouGov is online), it does explain nearly all of the 3 to 3.5 points by which the two pollsters have typically differed in recent months.

Lord Ashcroft uses this ICM technique as well, however his national poll shows very few “Don’t knows”, so the adjustment is very small. Instead, his poll has a relatively high level of Lib Dem support before the adjustment. There is no obvious reason for this, but it’s notable that Ashcroft National Polls typically have among the lowest support for the Conservatives and Labour and higher figures for everyone else, including the Lib Dems.

Survation also performs a similar adjustment to ICM, but with 30, rather than 50, per cent of “undecided” and “refused” reallocated. However this is offset by the fact that Survation’s polls, which include UKIP in their main prompt, typically have by far the highest UKIP polling – 23% in their latest poll, including 27% of 2010 Lib Dems, compared to 12 per cent of 2010 Lib Dems in the YouGov poll – more than enough to offset the reallocation.

The record-low Opinium poll last week was interesting because it isn’t due to house effects – its polling, on average, shows very similar Lib Dem support to the industry average. Instead, the 5 per cent reading is four points lower than the more typical 9 per cent it reported 10 days earlier. Like all pollsters, Opinium weights responses by demographics, but unusually, they don’t weight either by past vote or party identification.

Demographic weighting does iron out some of the response bias that pollsters encounter, to the extent that party support differs across various demographic groups. But if differential response arises within a particular demographic, that feeds through into the results. That may explain the sudden Lib Dem drop on this occasion, but since Opinium don’t ask (or at least, don’t publish) a past voting breakdown, we can’t say for certain.

Of course, we don’t know which approach provides the most accurate snapshot of how people would vote in an election, but we can see that the snapshots are quite different.

(continued…)