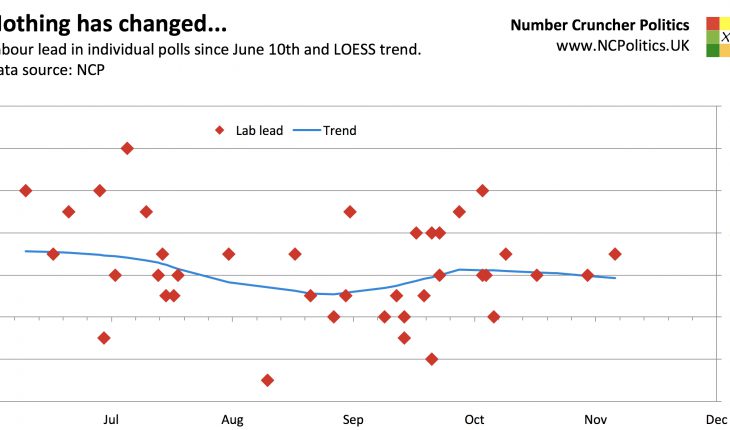

For the last few months, one question seems to come up repeatedly when a new poll comes out – why aren't the polls moving? This has intensified in the last couple of weeks as the sleaze and crises in Westminster have mounted, yet none of it seems to be having any effect, despite the widespread presumption that the government is in trouble.

Ipsos MORI/Evening Standard:

CON 38 (-2)

LAB 40 (-4)

LD 9 (=)

UKIP 4 (+2)

GRN 3 (+2)

SNP/PC 5 (+1)27-1st

N=1,052https://t.co/qlRpubkNAg— Number Cruncher Politics (@NCPoliticsUK) November 3, 2017

YouGov/Times:

CON 40 (-1)

LAB 43 (=)

LD 6 (-1)7th-8th November

N=2,012

Writeup @SamCoatesTimes https://t.co/UCgXlzgx14— Number Cruncher Politics (@NCPoliticsUK) November 10, 2017

Firstly, I should highlight a couple of technical reasons why polls are less volatile, both than they used to be, and compared with polls in many other countries. Firstly, sample sizes have increased over time. Sample size has an inverse square root relationship with the margin of error, so if you double the sample size, you reduce the margin of error by about 29 per cent.

Also, and perhaps more significantly, polls use much stricter quotas and heavier weighting than they used to. In technical parlance, they are more stratified. Weighting respondents’ past votes to the results of the last election (and the EU referendum) is now commonplace in Britain. If a sample has a consistent balance of left and right, open and closed, and so on, it won’t be pushed around by one party’s supporters being keener than another’s to the extent polls used to be, or still are in say, the US.

But that’s not the full story. Ipsos MORI’s poll for last Friday’s Evening Standard is one of the few that doesn’t use that type of weighting, and has a sample size of a little over 1,000, yet its results too were stable.

Likewise, last night’s local by-elections, though tricky to interpret due to changes in candidature, didn’t look bad at all for the Tories, even in London, considering how poorly they did in the capital back in June. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that public opinion itself has genuinely been rather static.

Why might that be? The most common explanation on psepholoical Twitter is that people are “tuning out”. That’s intuitive because the main policy issue at the moment is Brexit, a lengthy process that doesn’t lend itself to “new news” very often. After all, if Matt Chorley is bored with Brexit, there probably isn’t much hope for the person on the street.

Next, the fundamentals haven’t shifted much. MORI’s gross satisfaction ratings, the spread of which tends to be a very strong predictor of election results, moved dramatically in the runup to the election, but have barely changed for either leader since (other pollsters have found broadly similar patterns).

This chart is quite telling. Gross satisfaction levels for both main party leaders moved dramatically during the campaign, but little since. pic.twitter.com/v0DoI4z3Kr

— Matt Singh (@MattSingh_) November 3, 2017

The fact is, although Jeremy Corbyn’s personal numbers are now higher, both in absolute terms and relative to Theresa May, there are still plenty of voters that haven’t warmed to him. Does that mean there’s a “ceiling”on the Labour vote and a “floor”under the Conservative vote? I don’t know. But if the opposition can’t make significant ground given all of the tailwinds it currently has, it’s possible.

Which of these two it is matters for what happens next. If it’s people tuning out, then the Tories getting their house in order probably wouldn’t help them much. If it’s a ceiling and floor type scenario, it probably would.

Fair question from @MattChorley…https://t.co/ZLn5JovqyG pic.twitter.com/1uvzFpA9Ze

— Matt Singh (@MattSingh_) November 10, 2017

Consider too the question of electoral polarisation, something that Glen O’Hara calls a “cold culture war”. This is another fair point, and given that so much of the polarisation is linked – either directly or indirectly – to Brexit, the aforementioned “boredom” issue comes into play, because peoples views on Brexit aren’t changing much either.

What seems less likely is the suggestion that it’s just the Leavers propping up the Conservatives. In recent polls about 40 per cent of Leave voters that would vote are not saying they would vote Tory, and about 30 per cent of Remainers are. Both of those numbers have been stable for months.

And as ever, there’s the matter of salience – even if people are paying attention, do they care? Remember Theresa May’s conference speech, or Gordon Brown calling Gillian Duffy a bigot? In both cases, the Westminster bubble went into overdrive in response to a supposedly earth-moving development, yet the public were unmoved.

That brings us to the major issue of late, namely the string of allegations and admissions of inappropriate behaviour by MPs and others. I’ll write more on the subject of scandals and their effects in another piece, but suffice to say that this one is, ultimately, a cross-party issue. You can argue about which party is most implicated, which is coming off worse and which is handling it better, but it’s certainly not a single-party affair.

What’s more, the salience gap between Westminster and the average voter is probably even bigger when the story in question is itself set mostly in Westminster.

Putting all of this together, I don’t think it’s just one thing holding the poll numbers steady. It feels like a combination of several inertial forces, combined with the fact that the public have yet to be convinced to change their minds.