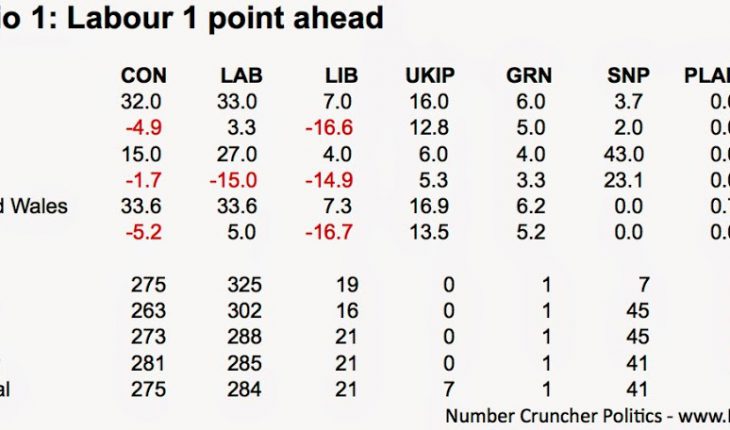

Finally a bit of historical context, with the current estimates for comparison. To estimate the skew at past elections, I’ve taken the actual results and applied a uniform swing to Labour and Conservative vote shares to equalise their seat numbers.

As we can see, the skew was practically nonexistent in the 1980s, but opened up to 3.6 points in 1992. Part of this was due to tactical voting, but more of it was due to the national LIB-LAB swing, which cost the Conservatives 40 seats, despite their vote share being only very slightly lower than in 1987. In 1997 the skew increased further, as turnout in safe Labour seats dropped, distributing Labour’s vote more efficiently. 2001 saw a continuation of this, which combined with the incumbency effect for the 1997 intake of Labour MPs, pushed the skew up to its high watermark of 7.8 points.

2005 saw the start of a reversal, as Lib Dem supporters who had tactically voted Labour in prior elections returned home, and others switched, causing Labour to lose 47 seats and the Conservatives gain 33, despite the latter achieving an increase in its vote share of less than a point. The skew tightened further in 2010 due to the expected close result helping to equalise turnout across constituencies. The 2010 skew was about 4 points to Labour. About a point of this was due to favourable boundaries and a further point-and-a-half can be explained by differential turnout in safe seats.

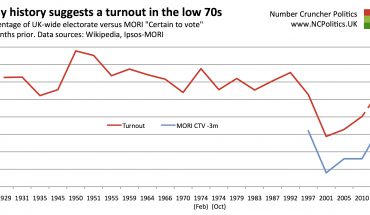

Neither of these factors is included in the above analysis. The boundaries haven’t changed for 2015, so historical experience suggests that demographic shifts are likely to move the votes-seats balance slightly towards Labour, but probably only very slightly. Against that, differential turnout (or, frankly, anything related to turnout) isn’t easy to predict, but with parties like UKIP, the SNP and the Greens on the prowl, the effect of the differential in safe seats is likely to be reduced. Put another way, a seat that has traditionally been safe from the other ‘big two’ party might not be quite so safe from other opponents. This shouldn’t be overplayed – the risk of a Heywood and Middleton-type situation in a general election isn’t particularly high, and won’t lead to ‘indyref’ turnouts in Labour heartlands, but I’d be surprised if it had no impact on turnout whatsoever.

Tactical voting is a whole other area. The fact that there are so few remaining Lib Dems in LAB-CON marginals (low single digits in Ashcroft polling) suggests that in most of those seats UKIP voters are likely to be far more important. Will they vote tactically, and if so, what will they do? I shall revisit tactical voting in due course – this analysis doesn’t build in any net effect. Nor does it account for more complex differentials in swing (for example, between different types of Scottish seats). Again, this might warrant revisiting when Lord Ashcroft’s Scottish polling is published.

For now, it looks like the party winning the most votes will also win the most seats.