The debate about polling methodologies for the EU referendum took a heated turn on Friday, with YouGov’s former President blogging that online polls were getting the referendum wrong, followed shortly by the company posting analysis claiming to have evidence that phone polls were wrong.

It’s not my intention to inflame the exchange any further, but as co-author of the study at the centre of the row, and following repeated requests for comment, I feel it’s right to set out my opinion.

To be clear, none of what I have written has been meant as an attack on either mode, and certainly not on any pollster. Moreover, I don’t claim, and have never claimed, that my conclusions are definitely right and that others are definitely wrong. That would be arrogant and unhelpful. No-one knows for certain which method is closer to the truth, so all anyone can do is offer a data-driven view of the likeliest scenario (which in this case means data that are a couple of months old). And while my view is always subject to change in the light of new evidence, it has not been changed by this latest analysis.

YouGov’s criticism of phone polling centres around the oversampling of people with high levels of education, based on figures drawn from the tables of the polls from Polls apart, which conducted two parallel tests earlier this year. At first glance, their thesis seems compelling – there are too many graduates in the sample and graduates are solidly for Remain, therefore (the theory goes) phone polls must be understating support for Brexit.

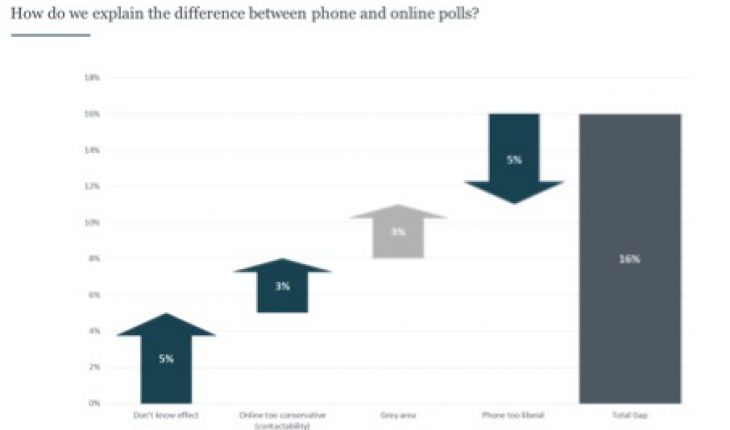

As James Kanagasooriam and I explained in Polls apart, the evidence did indeed suggest that phone samples were a bit too socially liberal (and therefore pro-EU) and we were aware of the oversampling of graduates. These are essentially two sides of the same coin, as they are highly correlated. Therefore the solution that we proposed, which reduced the 14 point lead in the original version of the poll to 10 points, fixed this imbalance.

The YouGov piece noted that without the underlying data it is impossible to reweight sample to adjust the proportions of graduates. Yet YouGov tried to do it anyway, or at least, they attempted to estimate the impact of the apparent skew. Neither NCP nor Populus were approached to request the actual numbers before publication, which seems odd.

YouGov’s back-of the-envelope maths suggested that reweighting would dramatically reduce the Remain lead. Actually, it reduces it by just 3 points to 11 points, if we use the “standard” methodology (weighting by demographics and past vote).

Essentially, weighting down the proportion of graduates to the 30% or so in online panels does roughly the same thing the attitudinal fix we proposed, which reduced the Remain lead slightly more, to 10 points. If we apply educational weights on top of these, the additional impact is tiny – the Remain lead is still 10 points.

The reason why what looks like a huge bias has, in fact, a relatively small impact, relates to the correlation between weighting variables. Modern polls are weighted using an algorithm called RIM weighting, also known as raking. I’ll spare you the technical detail here, but essentially it’s a (very useful) way of ensuring that a sample as a whole matches various nationally representative targets, without the arithmetic impracticality of weighting within every cell. For example, a poll will have the right proportions of men, ABC1s and 2015 Conservatives, but among male ABC1s there might not be the right proportion of 2015 Tories. It’s usually a minor issue, because it will tend to be offset by an error somewhere else, so we can generally trust the overall numbers.

But it does mean that if there are too many graduates, they usually won’t have been oversampled equally across the board. That means that “unskewing” polls, Dean Chambers style, will often wildly exaggerate the effect of changing the proportions of different types of voter. In other words the graduates that need to be weighted down are quite Leave-y, relative to other graduates, while the non-graduates being weighted up are relatively Remain-y.

Incidentally this weighting procedure also explains why crossbreaks within poll tables, which some people on social media like to cherry-pick, are often misleading. Even if you can aggregate polls to get an adequate sample size, a poll of Great Britain is representative of Great Britain, but not necessarily of each and every geographic or demographic crossbreak within it.

The article then went on to suggest that there must have been something fishy going on with the March sample, because the education crossbreaks on the February sample showed something more in line with what its thesis suggested. This argument, however, is based on what appears to be a misread of the tables.

Unlike the March poll, the February poll was divided into samples A and B. The reason for this, ironically, was to split test a hypothesis put forward by YouGov among others, that the presence or absence of a “don’t know” option explained some of the phone-online polling disparity. It did, and having the undecided option that isn’t on the ballot paper (and isn’t normally present on phone polls) hurt Remain very disproportionately. The 48-37 headline figure that YouGov quotes is derived from split sample A, which used the normal methodology. But the educational crossbreaks are for the two samples combined, so the comparison is not apples-to-apples.

Some will wonder whether it wouldn’t have been simpler just weight down the proportion of graduates. Yes, it would, but remember this was a parallel test, and we presented our fix using the same weighting variables in the phone and online samples. Using educational weighting did not explain very much of the gap, because the skew in online samples is not demographic, but attitudinal. Had we been working on a production fix for phone polls, our approach would have been different.

In short, phone polls probably are a bit too much towards Remain, but only to the extent that we identified in Polls apart. The “bombshell” is not a game changer in terms of explaining the modal difference.

Sunday politics on #EUref polls with @MattSingh_, @martinboon, @benatipsosmori & @JoeTwyman talking to @reporterboy, https://t.co/V88EM0qEKu

— NCP EU Referendum (@NCPoliticsEU) 22 May 2016

But what about YouGov’s phone poll, that showed Leave ahead? YouGov released the tables as usual, but also took the unusual decision to release the full microdata. I suspect that this practice won’t catch on (given the cost of obtaining the data), but it does give us a chance to look at what they’ve done. The claim is that the sample is more representative because of repeated callbacks and a two-week window. The two-week claim is technically true, but consider the following: 57% of the fieldwork was done in a three-day block, and a further 29% was done in a two-day block. Seven days had ten or fewer interviews.

Interestingly, all five “busy” days were weekdays, with only 7% of the fieldwork done at weekends. Systematic differences between weekend and weekday polling were something that appeared at various times when Populus published twice-weekly online polls in the last Parliament. But phone polls now almost always include very large proportions of weekend fieldwork, simply because many people are only available then. The impact of polling almost exclusively this is unclear.

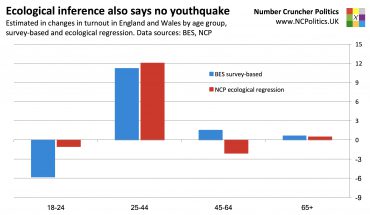

YouGov also said that it didn’t set quotas, but instead tried to maximise response rates through the callbacks, like the British Election Study did. This is fine, as long as you do eventually get a very high response rate and a representative raw sample, as the BES did.

Phone pollsters don’t normally publish response rates, and the newest member of the club is no exception. But it’s well known that initial response rates are typically around 10 percent or lower. And crucially, based on the work that I’m aware of, they do not increase markedly with callbacks. This is very different from face-to-face polling, seemingly because the problem isn’t just getting hold of people, it’s also persuading them not to hang up, but to participate for no financial reward (and in the case of mobile users, not to screen out calls from unknown numbers). Differential refusal is therefore in addition to differential availability.

The YouGov analysis mentioned raw samples in relation to the oversampling of the ABC1 social grades in some phone polls, which is an important point. But as a likely consequence of the above methodology, the raw sample in their phone poll is wildly unrepresentative in a number of areas. It has far too few people educated to 20+, too many over 65s, too few people in London and too many people in less affluent regions. These imbalances are mitigated through weighting, but the weighting required is unusually severe for a phone poll, so the effective margin of error increases further.

These observations don’t necessarily explain why the result is so far out of line with other phone polls – it could be something else that isn’t immediately obvious, but this poll clearly isn’t representative of phone polls generally, so I’m not entirely sure what to make of it.

The study also made a few other points. It suggested that the results of the last general election contradicted our claims about social liberalism versus conservatism in samples. They did not. As James and I made clear in Polls Apart, we are talking about the element of social attitudes that doesn’t correlate with partisanship. That is pretty fundamental.

YouGov does now appear to accept high quality probability surveys like the BES and BSA as the gold standard. It is telling that the BES question on EU membership produced results closer to what comparable phone polls were showing at the time. YouGov points out that in the time since, it has made methodological changes. But – and I’ve said this a few times – our study was of differences between modes, not differences between pollsters. YouGov is not the only online pollster.

Yougov’s changes look like they’ve worked, and improved their samples. But the apparent underlying problem for online panels generally, was very much in evidence when we researched Polls apart. Across demographic cells, we noticed a residual attitudinal bias.

To summarise, this paper is an interesting contribution to the debate, but I can say with confidence that it does not find the holes in the Polls apart work that it claims to.